Day One: Silver How

After weeks of drought, hosepipe bans in the Northwest, and endless sunshine, we all braced ourselves for a Caribbean-like “Lakes 5 days”. Upon arrival at the M6 assembly area near Kendal, the bracing winds and drenching showers were at odds with our shorts, shades and flip flops that had accompanied one of the driest summers on record. No one really expected it not to rain in the Lakes, and our pessimism sadly was well founded, as Day one on Silver How was a baptism of fire for everyone, especially the youngsters and those new to orienteering on the fells.

Grasmere is synonymous with Wordsworth; his evocative poetry of his charming Lakes, and his perfect Grasmere were battered and soaked by heavy rain, strong winds, and dense mist. If it wasn’t for the eagerness to start the festival, many of the orienteers might have given this day a miss, and some did. We were drenched by the time we had climbed up to the 300m start (2.5km), and I was full of trepidation about sending the girls up into the gloom of a Lakeland fell to fend for themselves in the banks of rolling mist.

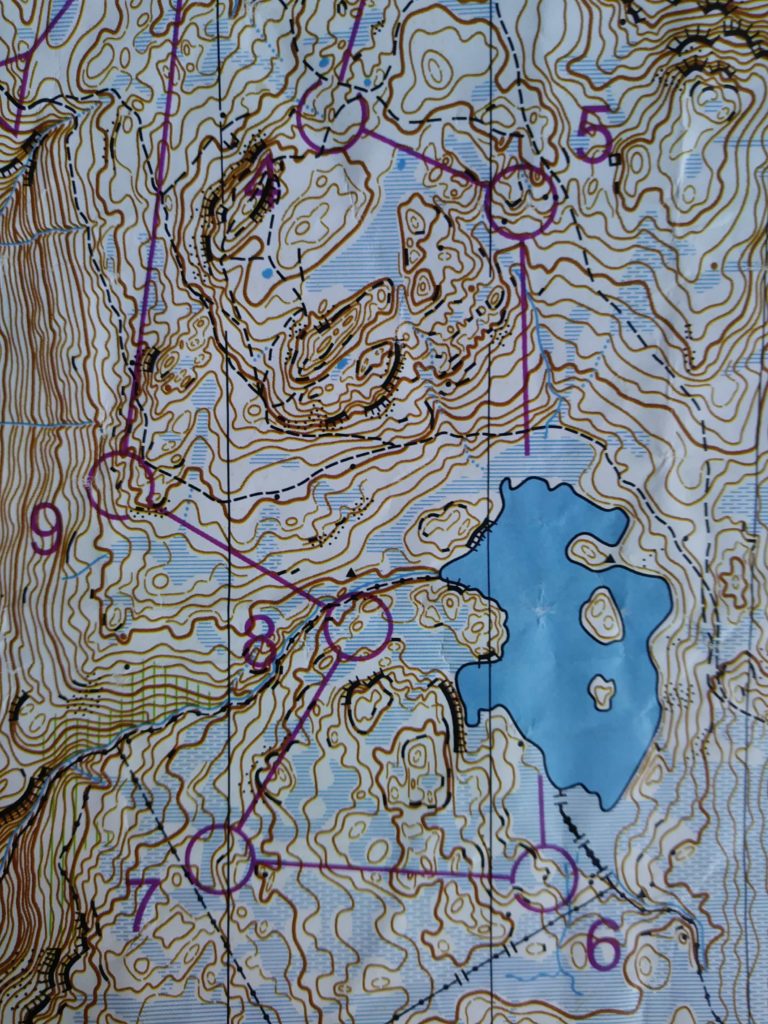

Like a huddle of Emperor penguins in a particularly fierce, albeit warm, Antarctic blizzard, the assembled soak of runners vied for shelter on the exposed fellside. The start team kindly obliged with early starts, and before long we were all out on the fell, focussing on contours, marshes, crags and boulders. The map and course were technical, the mist added a challenge that favoured the navigator, and the communal absurdity of the conditions engendered a sense of camaraderie that a sunlit warm day would never have permitted. Fellside orienteering in mist requires precision map contact, where small crags rear up through the gloom like towering buttresses. The small collection of tarns, and the main path to Blea Rigg, provided some reassurance for relocation, but the tangle of Silurian lumps, bumps and crag faces could, if not careful, become a jumble and led to costly mistakes.

The intrepid river crossing from the finish to download only added to the experience, and ensured everyone went home with wet feet. The queue of dripping orienteers at download, laughing at the local orienteers who insisted that Cumbria had actually suffered a drought, was brought to a conclusion by a generous gift of Grasmere gingerbread.

The open fellside of Silver How proved tricky in the howling wind, banks of mist and driving rain.

Day Two: Angletarn Pikes

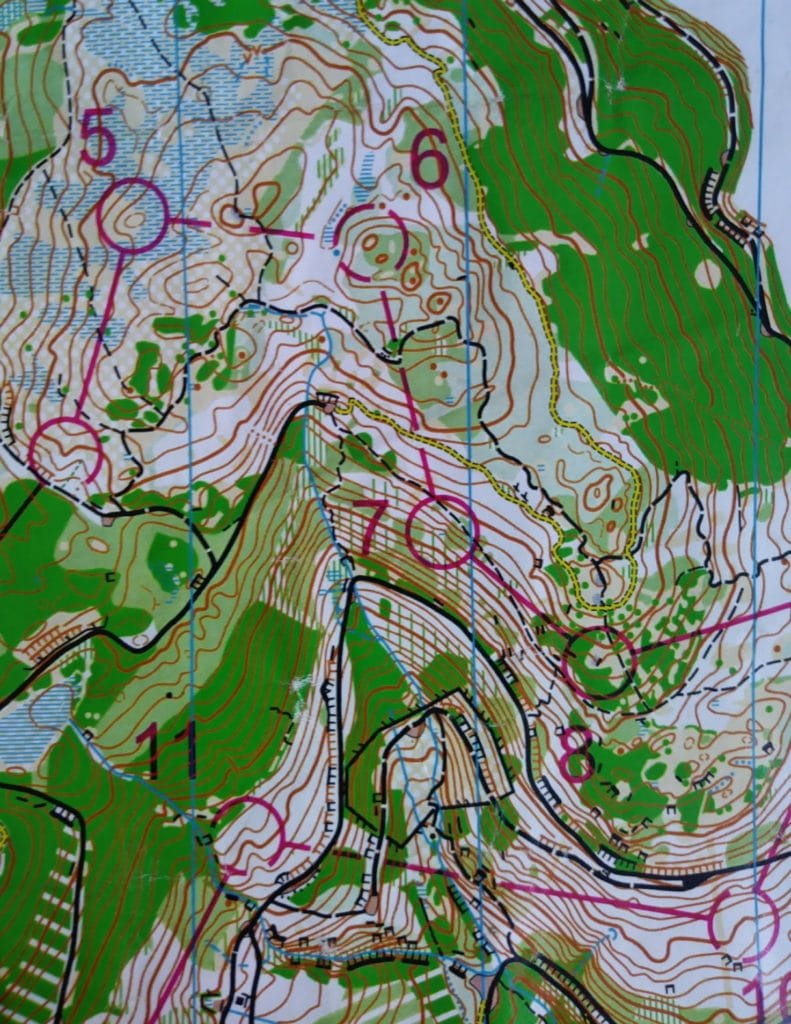

The heavy rains had temporarily threatened the day two car park. Thankfully the positivity of the local farmer and organisers meant that the roadshow moved onto Ullswater. The endless ant-trails marched up and down Boredale Hause for the best part of 4-5 hours, on the way to and from the lofty and exposed start/finish on the western flanks of Angletarn Pikes. The views down over Ullswater, Brothers Water and across to the cloud-capped Helvellyn were classic Lakeland. Save for a brief cloud burst later on most people enjoyed a fast and furious romp over a lesser known, but intricate fell, and may even have got a bit of sunburn. The contrasting clear views favoured the runners, with navigation far less of a challenge than the previous day. The courses were again excellent, with visits to the tarns and marshes to the south, and the intricate topography near the finish ruining many a run, particularly where margins were tight. It would have been nice to sit atop Angletarn Pikes and bask in the sunshine, with a fine view over one of the most attractive tarns in Lakeland, but sadly with orienteering, we do spend too much time rushing around, with our head glued to the map. At one point I opted for a more scenic route along the escarpment, purely just to enjoy the beauty of this delightful corner of Lakeland.

A glorious day exploring Angletarn Pikes and its delightful tarn

Day Three: Whinlatter

After two days on the fell, we moved to the forest of Whinlatter, with its darkened plantations, steep hillsides contoured with forest tracks, and its lofty heathery moors. The starts were ideally placed to make the most of the rarely frequented Lord’s Seat, Whinlatter Top and Broom Fell. Clear open running ought to favour the runners, but anyone who managed to leap over the endless bounds of heather deserved a medal, and bionic thighs, as the going was tough. Back in the forest, the denizen of the Gruffalo, the courses utilised the fast forest tracks, a network of non-permitted cycle tracks [which looked like normal paths until you saw a cyclist], and a grandstand sprint finish to the encampment of club tents nestled among the pines. This was one of the warmer days, and for all the dreariness of intensive forestry, Whinlatter provided excellent views over Bassenthwaite and Keswick, towards the towering bulk of Skiddaw. After 3 days it was time for a rest, appraise the scores so far, and for some to dash around the streets of Ulverston. We preferred a spot of pitch and putt, and red squirrel watching.

Energy sapping heather moorland and dense plantations at Whinlatter

Day Four: Askham Fell

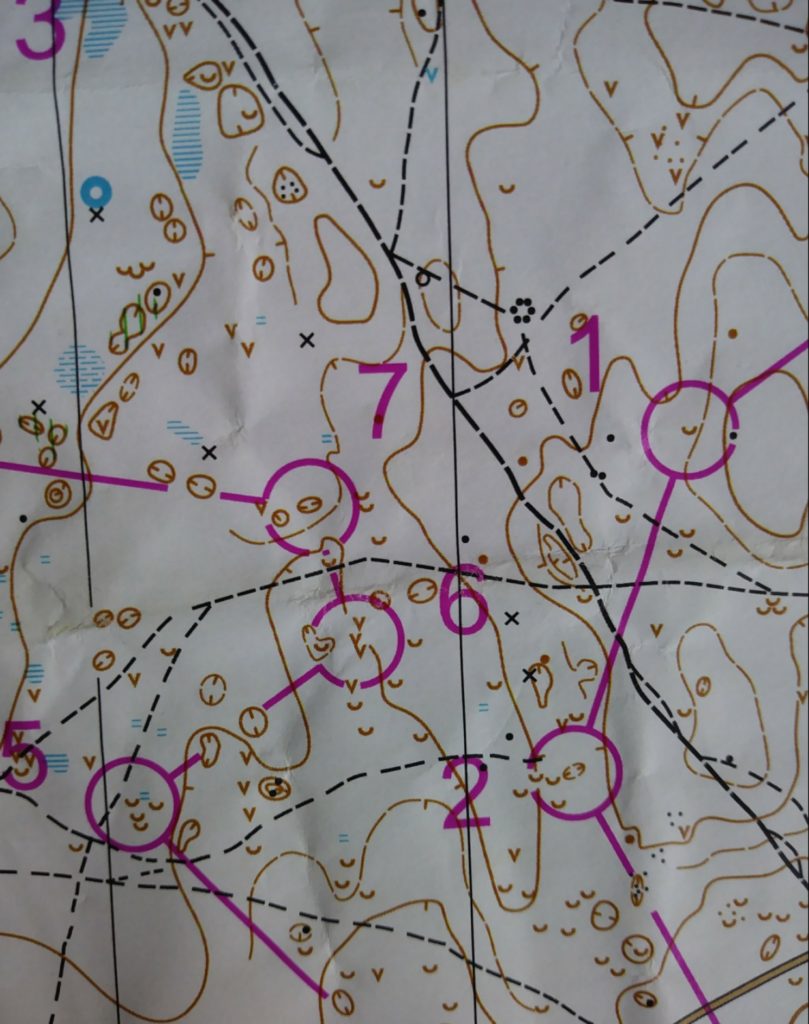

Waking with sore limbs, day four was on the open moorside of Askham Fell. Wainwright wrote that Askham fell was “positively the worst bog on any regular Lakeland path. Avoid it!” Not so on this occasion, as the dry weather had drained many of the marshes. The landscape here was more akin to the Yorkshire dales, with Carboniferous limestone underfoot, and an endless network of sinkholes, and stones of antiquity. People roamed Moor Divock many thousands of years ago, a far cry from the lycra-clad navigators of today, but little did they know that their burial mounds and cairns would add such value to our entertainment. The lack of linear features across the moor made long range compass work a risky business. Navigating from sinkhole to sinkhole as handrails appeared to prove the most successful tactic, and any loss of map contact made for problematic relocation. The ubiquity of these large depressions, and the large numbers of visible runners and controls meant that following others was a dangerous tactic, but heading for bracken filled holes permitted some form of assistance, as did the increasing number of elephant tracks as the day wore on. The final few controls followed a narrow gorse dominated valley, with precious seconds lost amongst the thorny tangle of vegetation. The warm sunny weather, the distant views of the Pennines and the assembled throng of happy people made for an extremely pleasant day in a quiet corner of the Lakes.

A Carboniferous puzzle of sinkholes on relatively flat moorland

Day Five: Dale Park

The last chance to improve on the “discard day”, or sneak a podium place awaited all at Dale Park in south Lakeland. After two relatively contour free days, with “easy-to-read” maps, day five was a premier test of fitness, navigation and eyesight, whilst running through a power shower. The feature-packed woodland was so complicated the mappers generously provided 1:7500 maps. As billed this proved to be the most technically challenging day, and there were many grumbles at the assembly on how testing the courses had been, the difficulty underfoot, and the costly mistakes that had been made. The rain had returned, making the ancient woodland and its jumble of crags, re-entrants and boulders slippery and extremely difficult to gain much pace. The runners benefitted little, however this was a day for those with titanium ankles and precision navigation. This was premier league orienteering, and although distances were short (i.e. middle distance), the times were not quick. I imagine this was more Swedish forest than Lakeland, and it proved to be a fantastic final test to determine the best orienteers of the week. In true Lakeland style the rain added to the sense of achievement, and brought to an end a thoroughly worthwhile holiday, where expectations were exceeded, and with differing skills tested over the course of five (six) superb days.

A steep ancient Lakeland woodland, with confusing crags and re-entrants